The Cost of a Broken System

The statistics are staggering. Despite decades of effort, less than 10% of all plastic ever produced has been recycled. The rest clogs our oceans, fills our landfills, and represents not just a colossal environmental failure, but a market failure that has left hundreds of billions of dollars in material value unrealized. But to understand this failure, we don’t need to look at global supply chains; we only need to look at a single shelf in a convenience store.

Consider the simple water bottle. Here is one made from clear PET. Next to it, one made from a bio-plastic, PLA. A third is opaque HDPE. Each has a different cap, a different label, and a different adhesive holding that label in place. We call this “consumer choice,” but from a systems perspective, it is chaos by design. While each bottle may be technically “recyclable” on its own, together they form a recycler’s nightmare—a stream of contaminated, incompatible inputs that are immensely costly to separate. This is the core of the problem.

This systemic chaos is not an unsolvable issue of waste, but a solvable problem of design. To create a thriving market for recycled plastics, we must stop chasing waste and start architecting a new system from the ground up.

The “Waste Management” Fallacy

For thirty years, the prevailing wisdom has been to treat this as a “waste management” problem. We have invested billions of dollars in the back end of the process: building more advanced sorting facilities, developing better chemical recycling methods, and optimizing collection logistics. In essence, we have spent our resources trying to manage the chaos after it has already been created. This is like building a world-class hospital at the bottom of a cliff instead of simply putting a fence at the top. It’s a noble effort, but a strategically flawed one that treats the symptom, not the disease.

Of course, it is essential to acknowledge the valid business drivers behind this complexity. Brand identity is tied to packaging, performance requirements demand different materials, and a free market allows for competitive sourcing. These are not trivial concerns. But a myopic focus on front-end differentiation has inadvertently crippled the back-end of the entire value chain.

The Turning Point: A System Design Problem

The fundamental flaw in our thinking is this:

This has never been a waste problem; it is a system design problem.

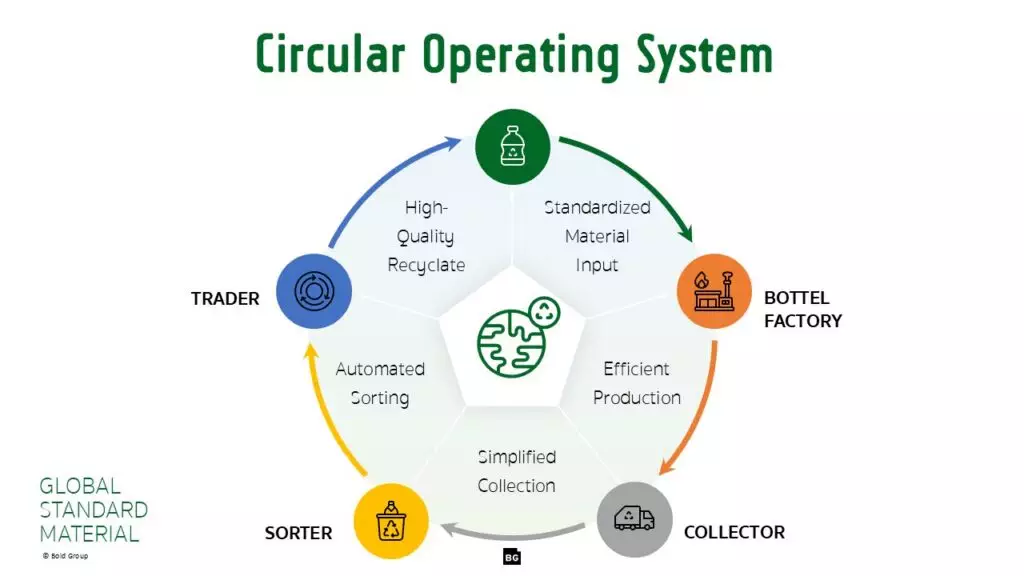

At BOLD Group, we believe that any complex challenge, whether in a product pipeline or a global supply chain, can be solved by applying rigorous architectural principles. The solution to the plastics market is to stop looking at the end of the pipe and to redesign the system itself. We propose a new way of thinking: The Circular Operating System (OS).

Just like a computer’s OS manages how all applications work together efficiently, a Circular OS is a set of guiding principles, protocols, and enforced standards that govern the entire value chain. It’s not a piece of software, but a way of working that ensures all participants—from polymer producer to brand to recycler—operate from a shared playbook. Its primary function is to preserve the value of materials throughout their lifecycle.

The “code” for this OS is a common standard. Let’s apply it to our water bottle problem.

Rule #1: All non-carbonated water bottles under 1 liter will be made of clear PET type 1, with a compatible HDPE cap and a non-contaminating adhesive.

This single, enforced rule doesn’t limit competition on brand or water source, but it transforms the end-of-life economics by architecting simplicity at the source.

The Resolution: Architecting a Thriving Market

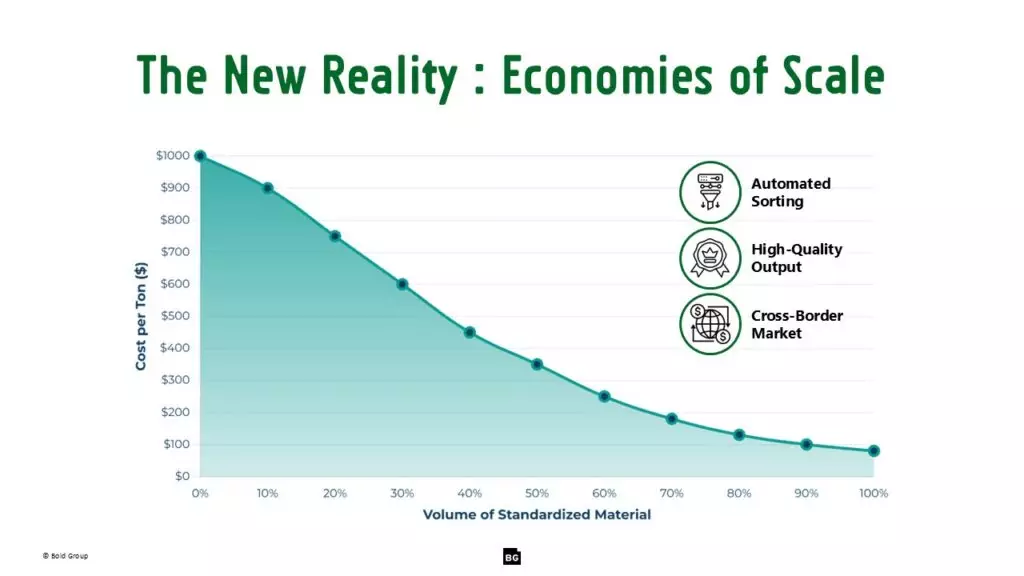

When the inputs to a system are uniform, the results are transformative. By implementing a Circular OS, the cost of collection and recycling plummets. Sorting, once a complex manual task, becomes largely automated. The output is no longer a contaminated mess of mixed plastics, but a predictable, high-quality stream of recycled material.

This high-quality material is no longer “waste”; it is a reliable, tradable commodity. This is the key that unlocks a thriving, cross-border market where manufacturers can confidently purchase and use recycled plastics in their own production, closing the loop and creating a truly circular economy.

In our work architecting innovation capabilities for global companies across 46 industries, we see this pattern constantly. A well-designed system delivers predictable, high-quality results. The principles that allow a technology company to launch new products on a reliable schedule are the same principles that can create a reliable supply of recycled materials.

Your Next Move

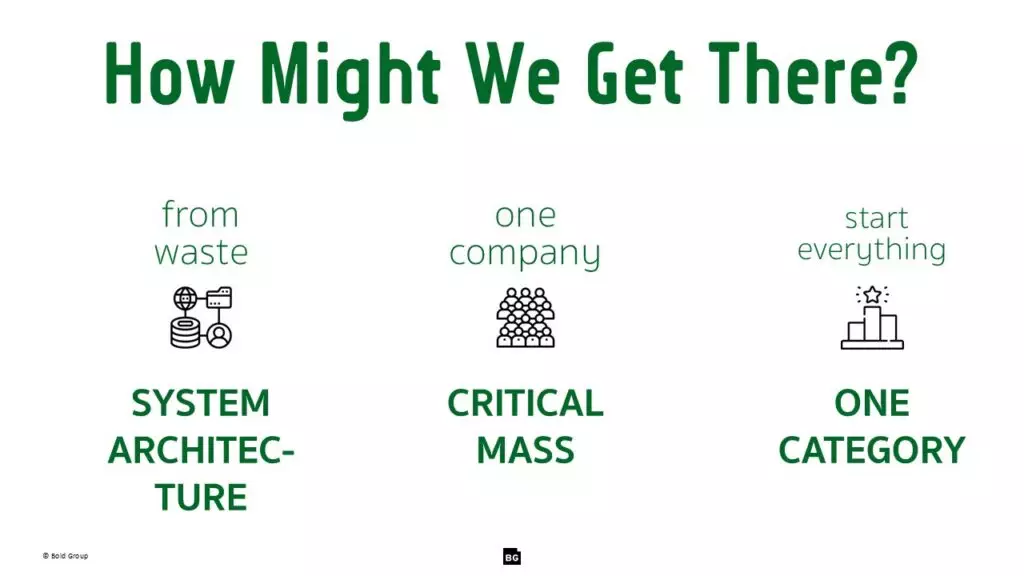

Just as our digital world runs on operating systems like iOS and Android, our future circular economy must be built on a robust, shared OS for materials. This transformation requires a new kind of leadership and cross-industry coordination. It starts with three key actions:

- Reframe the Problem: Within your organization and with your partners, stop talking about “waste management” and start talking about “value architecture.” Frame the lack of standards as a critical business risk and a barrier to a profitable new market.

- Convene a Pilot Working Group: This cannot be solved by one company. A critical mass of industry leaders must come together to agree on the value of a shared system and commit to co-funding a pilot program.

- Architect a Pilot Blueprint: Don’t try to standardize the entire industry at once. Start with a single, high-impact category like water bottles. Formally architect the “Circular OS” for this category—defining the standards, the enforcement, and the metrics for success—and prove its value on a regional scale.

This article is part of Teerasak's talk at Switch to Green: Sustainable Value Chain for Recycled Plastic event by ASEAN ACCESS LEARN on the topic “Develop common standards enable cross-border trade and enable recycled plastic market”